Newsletter Signup

The Austin Monitor thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Most Popular Stories

- Latest State of Downtown report shows the city core’s businesses and housing are in transition

- Cap Metro to shelve 46 new electric buses for a year after manufacturer bankruptcy

- Jesús Garza disputes allegation that he violated city ethics rule

- Mobility Committee hears public concern regarding expansion of MoPac

- Council gives first reading OK to major development on tiny slice of land

-

Discover News By District

In Austin, traffic safety improvements come to those who ask

Thursday, May 12, 2016 by Kate McGee

Traffic fatalities are down nationwide, but new research shows those declines are mostly among highly educated people. For those who have less than a high school diploma, the rate of death in a car crash has actually increased.

That doesn’t mean you’re a better driver if you have a college degree, but rather that the less education you have, the more likely you are to find yourself living in conditions that are more dangerous, says Sam Harper, an epidemiologist at McGill University.

“Typically, when things are generally going good for the whole population, most groups see a decline and the gap between the lower and the higher educated groups tend to narrow, but in this case we actually saw that this gap was actually growing,” Harper says.

Harper looked at the education level of people who died in fatal car crashes between 1995 and 2010, pulling thousands of death certificates from around the United States. (Death certificates list people’s education level.)

What he found was that people without a high school diploma are more likely to be in a fatal car crash than someone with a high school diploma. That gap grows larger when you include people with a college degree.

But figuring out why is a bit murky.

Those who have received less education tend to have lower-paying jobs and live in lower-income neighborhoods, where traffic conditions may be less safe. Also, the poorer you are, the less safe your car is likely to be.

“Mandatory frontal airbags, side airbags or rollover airbags,” Harper says. “There are things like automatic crash warnings, those annoying reminders that tell you to put your seat belt on, better lights in cars. People with lower education may not be able to get access to some of these design features.”

But many low-income families in Austin can’t afford a car at all, forcing them to walk, bike or depend on Austin’s public transit system. As KUT reported this week, walking can be dangerous in Austin, especially for people who are struggling.

Seventy-four-year-old Florence Ponziano lives in the Montopolis neighborhood, an area with the highest percentage of poverty in the city. Her home, known by some as “The Comfort House,” is a well-known place in the neighborhood. She’s regarded as the “Godmother of Montopolis,” and she spends a lot of her time volunteering and taking care of the neighborhood children and elderly homeless.

Her fence is covered in colorful beads and CDs that reflect light, and her backyard is a huge playground for the kids, with swingsets and tree houses. There is art, toys, food and clothing everywhere. Ponziano is like a lot of people who live in the Montopolis neighborhood.

“I can’t really afford to buy a car and the premium prices of insurance and everything,” Ponziano says, rocking back and forth in a rocking chair in her backyard.

Ponziano catches the 350 bus on Montopolis Drive. It’s the area with the highest percentage of poverty in Austin. She says it’s difficult to cross the road safely.

CREDIT KATE MCGEE/KUT NEWS

Ponziano is too afraid to bike in the neighborhood anymore and says sometimes walking can be just as dangerous.

“I walk to the store, just this one on the corner, and I teach the kids: ‘Go on the light,'” she says. “‘Wait until the light turns and the figure comes on, and then walk across.’ OK, I waited, too. I was halfway through and this car is turning, not even looking. I had to jump, and my whole leg was smashed up. And they didn’t even stop. The car behind them stopped to help me.”

Ponziano also depends on the bus, but she says the wait times are long, and they’re even longer if you need to take multiple buses.

“I’ve been all around different cities. The connections on the buses in Austin are horrible,” she says.

Most bus service ends at midnight, which limits options for many low-income residents without cars trying to get home from work or after a night of drinking. In Central East Austin, people are less likely to have a car than any other place in the city. Despite that, this area tends to have a higher number of households with DWI arrests compared to other Austin neighborhoods.

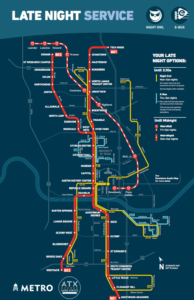

Cap Metro runs a Night Owl service until 3:30 a.m., but there are fewer routes and ridership is low.

CREDIT CAP METRO

“Where is the bus service that runs from Sixth Street after midnight? It goes to UT,” says Jane Maxwell, a UT Austin professor who studies substance abuse. She’s referring to UT Austin’s late-night E-Bus. “Would we see a decrease out in that neighborhood if there was a comparable bus service running at night?”

Capital Metro also provides Night Owl service that runs until 3:30 a.m., but there are fewer routes and ridership is low. Just one route runs through Central East Austin, and one route runs through Montopolis.

Maxwell also says that the less money you have, the less likely it is that you are able to take a cab or a ridesharing service to get home, which leads to more drinking and driving.

As Austin gets more unaffordable, many low-income communities have been pushed to the outskirts of the city, where high-speed roads were already built. But they don’t have sidewalks or bike lanes.

“Traffic safety touches people of all socioeconomic backgrounds,” says Tom Wald, who serves on the city’s Pedestrian Advisory Council. “But, when we’re talking about who are having to walk in these suburbs, oftentimes it is people of lower economic background. It’s young kids who cannot drive. It’s people who cannot drive. So, there are some disparities.”

There are various traffic-calming measures that the city can install on neighborhood streets to create safer routes for pedestrians, bicyclists and drivers. But for that to happen, often the neighborhood has to ask for it.

“It’s a request-based process, so we really wait for requests to come in,” says Jim Dale, assistant director at the Austin Transportation Department. “We are looking to be a bit more proactive in that in planning locations.”

Those requests can be as simple as a 311 call.

“We do not judge or weight any request more than another,” Dale says. “If there’s an active community and we get 30 requests for a pedestrian hybrid beacon in one location, that is no different to us than a location in another part of town that just got one.”

Duval Street in Hyde Park has speed bumps scattered along the street to slow down drivers.

CREDIT GABRIEL CRISTÓVER PÉREZ/KUT NEWS

In one of Austin’s poorest ZIP codes, Chicon Street remains a wide road with very few traffic-calming devices to slow motorists.

CREDIT MIGUEL GUTIERREZ JR./ KUT NEWS

But it does require people to know 311 is the place to call to request safety improvements. Transportation officials say they have banners around town telling people to call 311 when they have a problem and that they depend on the media to spread the word. Harper, from McGill University, says that sometimes, education campaigns require more nuance than that.

“They need to think about how literate people are, how numerate people are,” Harper says. “That they are able to get a firm understanding of the risks of whatever it is that they are going to be communicat(ing) to people.”

Using a request-based process also assumes that all residents have the time to be civically engaged and make that call or have faith in local government to actually fix a problem. That’s something Ponziano says is lacking among Montopolis residents.

“If the people don’t complain that they want something, they’re not going to do anything,” Ponziano says. “I guess we’ve had such little things done in our neighborhood for so long, people figure, ‘Oh well, they’re not going to do it.’ So they don’t bother calling.”

“I’ve been complaining for like 20 years, and like calling up that the lights — you can’t even cross the street in time,” Ponziano says. “And I’m very hyper and quick. So if I can’t cross the street in time, what about some old lady who walks really slow? ’Cause I’m really fast!”

All of this can exacerbate inequities between neighborhoods, making some safer than others.

“There’s nobody advocating for that infrastructure to be created,” says Lenore Shefman, a personal injury lawyer who represents pedestrians and cyclists who have been hit by cars. “The voice is less because quite frankly, people have less time to knock on doors at the legislature or City Council.”

Shefman says people sometimes forget that.

“You do the best with what you have, and if you need to be to work at 5 o’clock and you have to get your child to the babysitter and there is not (a) crosswalk for 2 miles, then you wait for a break in (traffic) and you run for it,” Shefman says. “And that, unfortunately, is something that people who don’t have to face that dilemma just really can’t compute.”

Pedestrian hybrid beacons are another new attempt to improve safety. Those are the red lights that pop up when a pedestrian presses a button to use a crosswalk. When one is requested, the city studies whether it’s a safe place to put one of these lights — they can’t be too close to a traffic light. The street has to be at least three lanes wide, so they’re limited to busy roads like Lamar or Airport. But there is at least one pedestrian hybrid beacon located on a two-lane road: It’s on Lake Austin Boulevard, right in front of the Austin Transportation Department.

This story is part of KUT’s series, The Road to Zero, which explores traffic deaths and injuries in Austin and the city’s plan to prevent them.

Top photo by MIGUEL GUTIERREZ JR./ KUT NEWS

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?