Austinites call for halt, and a vote, on CodeNEXT

Monday, September 11, 2017 by

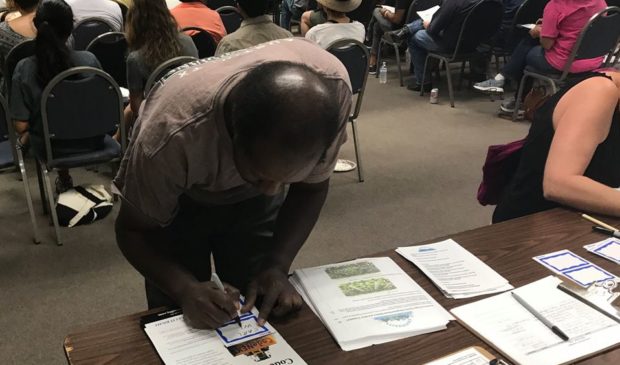

Chad Swiatecki Residents and activists in East Austin called for a halt and possible public vote on CodeNEXT during a community session Saturday where reparations for displaced individuals and a program to create affordable housing stock on city-owned lands were also discussed as possible solutions for gentrification focused in that area.

The session – titled “Destruction, Displacement, and CodeNEXT: Views From the East Side” – was organized by Community Not Commodity, and featured a panel of five academics and activists discussing the effects of racial displacement that kicked off with the city’s 1928 master plan, which called for African-American and Latino residents to be relocated east of I-35. With those areas seeing land values skyrocket in the past decade as Austin’s population has boomed, those in attendance Saturday charged that CodeNEXT and the Imagine Austin plan that informs it will leave the city with few housing options for middle- and lower-class residents.

“Unlike in 1928, there is no place for poor people in the new plan, with no areas dedicated for trailer parks, tiny homes and other options for affordable housing,” said Jane Rivera, chair of the Rosewood Neighborhood Contact Team and co-facilitator of Austin’s La Raza Roundtable. “We’ve wanted to see a dedicated fund to help people who are displaced and I don’t think that displacement is happening accidentally, so we have to take specific, targeted action to stop it.”

So far city officials have received the first of four three drafts of CodeNEXT, with the second draft due for publication on Friday. After revisions through the draft process, it is expected to be approved by City Council in April 2018, though a petition that started circulating over the weekend seeks to force a referendum vote before it can become official.

Among the city development policies discussed on Saturday, the practice of giving density bonuses to land developers in exchange for adding affordable housing units was heavily criticized for favoring young, single workers over families. The heart of that criticism was that affordable housing units, typically costing 60 percent of the median family income of the area, tend to be one-bedroom and studio units that can’t fit a small family.

Such practices and the demand for housing throughout Austin wind up increasing rents and property taxes and force working-class families to the city’s outskirts and beyond, said Eric Tang, associate professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas and director of UT’s Community Engagement Center. Tang said that dynamic is what has caused Austin to have a net loss of African-American residents in recent years.

“When cities grow at the rate Austin has, they shouldn’t see a loss in any racial group, but the black population was down 5.4 percent, and that sort of thing doesn’t happen,” he said. “The people (in 1928) never saw East Austin as being a prime site of gentrification, and that is what leads to the rapid displacement of that racial group.”

Council Member Jimmy Flannigan – who attended the session as an audience member – said he’d just learned about the petition drive related to CodeNEXT at Saturday’s session and wasn’t informed of the group’s intent to speak at length about it, but he said, in general, he is against May elections because they have lower voter turnout and cost the city around $1 million to conduct.

He also said he is interested in the idea to use city-owned land to construct affordable housing since the city has more land than it will ever be able to convert to parkland. He said Texas’ restrictions on some inclusionary zoning practices and linkage fees to generate revenue for affordable housing limit Council’s options on policy to encourage affordable housing.

“We’re struggling to make sure we’re making the right decisions for the whole city, and we know there will not be any version of CodeNEXT that will make everyone happy. No land use code will make up for generations of racism by the Councils in the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s and ’50s that codified racism in Austin. We need to work on this as a community together, and the fact that there are two intractable camps dug in this early in the process is frustrating.”

Photo courtesy of Community

Not Commodity.

Curious about how we got here? Check out the Austin Monitor’s CodeNEXT Timeline.

The Austin Monitor’s work is made possible by donations from the community. Though our reporting covers donors from time to time, we are careful to keep business and editorial efforts separate while maintaining transparency. A complete list of donors is available here, and our code of ethics is explained here.

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?