Newsletter Signup

The Austin Monitor thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Most Popular Stories

- Latest State of Downtown report shows the city core’s businesses and housing are in transition

- Cap Metro to shelve 46 new electric buses for a year after manufacturer bankruptcy

- Jesús Garza disputes allegation that he violated city ethics rule

- Mobility Committee hears public concern regarding expansion of MoPac

- Council gives first reading OK to major development on tiny slice of land

-

Discover News By District

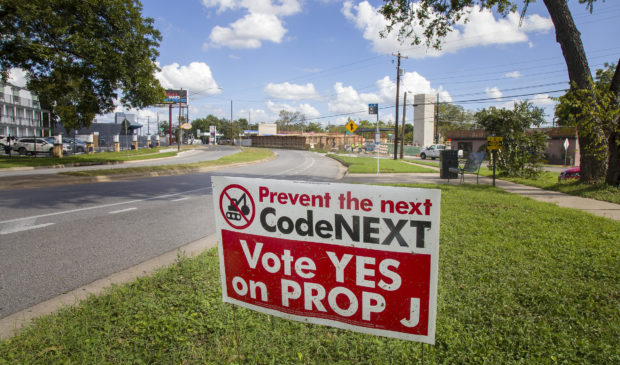

Prop J initiative exposes rift among Austin environmentalists

Tuesday, October 9, 2018 by Mose Buchele, KUT

Environmentalists in Austin worry about methane emissions from Texas oilfields, plastic pollution clogging up creeks and rivers or nuclear waste being shipped through the state. But one thing they rarely worry about is each other – at least until recently, when an initiative called Proposition J landed on the ballot.

Prop J would require that any comprehensive change to Austin’s land use rules go to voters for approval. As such, it would slow down and possibly scuttle big-picture rezoning in one of the country’s fastest-growing cities.

Opponents of Prop J say that would hinder smart growth and hogtie efforts to fight gentrification. Proponents say the opposite: They argue it will let Austin voters confront those challenges head-on.

Like any debate over Austin’s growth, this one touches on issues of affordability, gentrification and maintaining “neighborhood character.” So here’s a warning: This story won’t spend a lot of time on that stuff.

This story focuses what Prop J means for the environment.

CodeNEXT Backlash

It’s important to remember that the fight over Prop J is a continuation of a fight over density that began with CodeNEXT.

CodeNEXT was an overhaul of Austin’s development rules that would have allowed more density in some parts of town. A lot of people said it didn’t go far enough. Many others said it went too far. Eventually, the fight got too fierce for Austin City Council, so the mayor, who is running for re-election, announced that the city was putting the brakes on CodeNEXT.

But not before CodeNEXT opponents had put Prop J on the ballot.

“If Proposition J passes,” environmentalist Bill Bunch said, “then the voters will have the right to check the Council’s work if we resurrect CodeNEXT and we have a comprehensive rewrite of our Land Development Code.”

Bill Bunch, executive director of Save Our Springs Alliance, says greater density in Austin could lead to increased flooding and hurt the urban tree canopy. Credit Miguel Gutierrez Jr/ KUT

Bunch, the executive director of Save Our Springs Alliance, said he was opposed to CodeNEXT in part because he didn’t like the added density it would have brought to Central Austin.

“The place to do that is on greenfields development,” he said. “Do it right at the front end rather than scrape our existing city neighborhoods and try to force it on top of existing communities.”

That position provoked a lot of pushback.

“It’s weird to point out disagreements among your friends,” said Luke Metzger, the director of Austin-based Environment Texas. Metzger, who supported CodeNEXT, is opposed to Prop J.

Again, it’s all about density.

“The fact is the city is growing; we can’t build a wall around it,” he said. “And the question is: Are we going to increase sprawl, increase traffic, or are we going to do it in a much more walkable, transit-friendly way and bring people into the urban core?”

… So Goes The Nation

The debate is part of a larger debate over what it means to be an environmentalist in the age of global warming.

“I think what you’re seeing now in Texas can be copied and pasted into not just California, but I think across the country,” said David Garcia, policy director at the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley.

Garcia said climate change has forced environmentalists to re-evaluate their attitudes toward urban development.

“You have this tension between environmentalists who have traditionally been opposed to different kinds of development,” he said, “and the idea that we need to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions.”

The tension exists because one of the main ways cities can fight global warming is to encourage density.

“It’s not controversial for researchers; it’s controversial for Americans,” said Kara Kockelman, a professor at UT Austin’s Cockrell School of Engineering.

Basically, density fights global warming by reducing energy use. That, in turn, reduces emissions.

“The ability to walk and bike – that saves a lot of energy right there,” she said. “And then having smaller homes and businesses and maybe sharing walls and ceilings, that saves a lot of energy.”

‘Neighborhood Character’

Still, the local impacts of density may appear to harm the environment.

Bunch and other Prop J supporters point out that denser development could lead to increased flood risk, hurt the urban tree canopy and cause some houses to be torn down and replaced unnecessarily.

Experts say those fears are overstated, though.

“A lot of environmentalists are at odds because they have traditionally opposed development for legitimate reasons,” Garcia said, “but now they’re having to make the choice to say: Should we be supporting development to achieve this broader goal of creating more housing in dense urban areas?”

Indeed, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report Monday urging “rapid and far-reaching transitions” in cities to hold back the most catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Looked at this way, the debate isn’t over whether density in Central Austin is good for the Earth. It’s over how much of it we’re willing to accept as a city that claims to care about climate change.

Luke Metzger, director of Environment Texas, says encouraging compact living downtown is good for the environment. Credit Mose Buchele file photo / KUT

There are plenty of things that we know are good for the environment, but we still don’t want to do. In Austin, the type of density advocated by Metzger and other Prop J opponents might be one of them.

Part of that goes back to what some call “neighborhood character,” a nonnegotiable position among many residents and local politicians that single-family neighborhoods in Central Austin are crucial to the city’s identity. Much of the debate over Proposition J hinges on how strongly one believes that.

Bunch said he can only imagine rare “exceptions” where the interests of single-family neighborhoods conflict with the interests of the environment.

Meanwhile, Metzger believes duplexes, commercial zoning and multifamily living in Austin neighborhoods are desirable even without the environmental benefit. He said those benefits make more density an imperative, though, “if we’re serious about being the leading city in America on addressing climate change.”

This story was produced as part of the Austin Monitor’s reporting partnership with KUT. Top photo by Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon/KUT.

The Austin Monitor’s work is made possible by donations from the community. Though our reporting covers donors from time to time, we are careful to keep business and editorial efforts separate while maintaining transparency. A complete list of donors is available here, and our code of ethics is explained here.

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?