How should Austin fund its transportation needs?

Friday, March 4, 2016 by

Jack Craver The City Council Mobility Committee largely steered clear of discussing a potential bond election during a meeting Wednesday focused on how the city can finance its looming transportation needs.

A bond election, said Council Member Ann Kitchen, who chairs the committee, “is not an inevitability.”

“It’s one piece that’s part of our discussion when we talk about all of our options for funding,” she told the Austin Monitor after the meeting.

Staff plans to present its proposal for a new Strategic Mobility Plan to Council in June, at which point Council will review the infrastructure priorities identified in the plan and consider how to fund them. It appears that it will be a challenge, to say the least, for the city to make serious progress toward funding the billions in needed infrastructure improvements without a major infusion of cash.

Howard Lazarus, director of the Public Works Department, told the committee that the city currently has $1.46 billion worth of missing sidewalks and that only 20 percent of existing sidewalks were graded as “functionally acceptable.” Another major need includes over $2 billion for improvements to I-35, and the city’s six major transportation corridors need $120 million in short-term improvements and $700 million in long-term improvements.

City staff indeed presented a number of alternative funding mechanisms, such as fees on various transportation uses or driveways. Public improvement districts could also be part of the solution, although they require the support of property owners in the district. If more than 50 percent of owners in an area support the establishment of one, they then pay fees that finance enhanced city services within the zone.

“It is a tool – we don’t see it as a tool that can significantly offset, for instance, bond costs,” said Greg Canally, deputy chief financial officer for the city.

Indeed, the ordinance that authorized the Austin Downtown Public Improvement District, for instance, called for the assessments to be used largely for security, maintenance of sidewalks, improvements to streetscapes and marketing of the downtown area, rather than major transportation investments.

Another financing tool at the city’s disposal is tax increment financing, in which the city invests public funds in a designated area for the purpose of stimulating economic development. The taxes collected through the increased property value are set aside to be used to further develop that district, rather than going to the typical taxing jurisdictions, such as the school district. The most prominent TIF example in Austin is the Mueller development, in which the city invested $65 million to turn the former airport into a multi-use development.

A TIF, however, is typically intended for small areas of cities, usually those that are judged in need of public investment to jump-start private investment. The investment by the city is supposed to be refunded by generating more tax revenue from increases in property values. It is therefore difficult to justify a TIF district simply to invest in typical upgrades to infrastructure that may not significantly raise the value of surrounding property.

Asked by Kitchen whether tax increment financing could be a tool for financing improvements to major transportation corridors, such as Burnet Road or Lamar Boulevard, Canally said that staff would have to assess “if those improvements are done, will they in themselves have a more positive impact on the values along the corridors than would have happened but for these (public) investments.”

Council Member Don Zimmerman repeatedly expressed concern that staff was proposing transit solutions that city residents, particularly those in his suburban district in Northwest Austin, don’t support. He noted that the previous Strategic Mobility Plan, approved in 1995, included a series of road improvements that he said have yet to materialize.

“I show my constituents the road plan, and they say, ‘Yeah, that kind of makes sense,’” he said, contrasting that with what he described as a stubborn insistence by city staff to pursue unpopular public transit initiatives, most notably the rail plan that voters rejected in a referendum in 2014.

Transportation Department Director Robert Spillar said that that plan was a guide, rather than a commitment to projects. The city has certainly not given up on major improvements to streets and highways, he said, but it would be hard-pressed to solve the congestion downtown simply through bigger roads.

The dramatic addition of business and residential development over the last decade, he said, demanded solutions that transport people into the urban core in a “more efficient manner.”

In comments to the Monitor after the meeting, Zimmerman bemoaned seeing city buses that are “90 percent empty” and suggested the city should do a study to see whether providing people with vouchers to use ride-hailing services, such as Uber and Lyft, would be more cost-effective than funding the bus system.

Zimmerman also argued that the congestion downtown is the result of flawed city policies that encourage densification. Austin is simply not a big enough population center, he said, to justify the mass transit systems that major metro areas, such as New York City, depend on. “It doesn’t make economic sense,” he said.

Suffice it to say, other Council members are more enthusiastic about expanding public transit.

“Public transit improvements absolutely are inevitable,” said Kitchen.

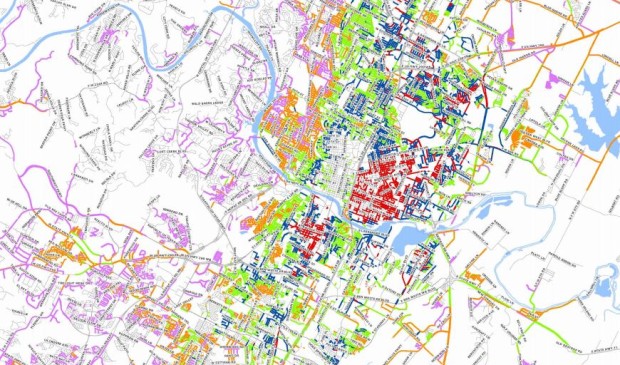

Map from the city’s Sidewalk Master Plan.

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?