Newsletter Signup

The Austin Monitor thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Most Popular Stories

- How Trump’s federal funding freeze is beginning to affect Austin

- APD won’t enforce SB 14 as Paxton and Trump further attack gender-affirming health care

- After shutting off mental health care for Austin musicians, SIMS Foundation restarts services

- Council approves call for better coordination, planning among downtown projects

- Austin ISD announces hiring freeze as budget deficit grows to $110 million

-

Discover News By District

Popular Whispers

- Council Member Mike Siegel will speak out against cuts to federal services

- City manager hosts community meetings on next year’s budget

- DAA offers a look at future of Sixth Street entertainment district

- RRCD names Klepadlo as executive director

- Zero Waste Advisory Commission adds own ‘no’ rec on merge with RMC

The decades-old theory behind speed limits might make it harder to change them

Wednesday, May 11, 2016 by Ashley Lopez, KUT

High speeds are one of the biggest killers on our roadways. As city officials tackle an uptick in traffic fatalities here in Austin, speed limits come up a lot.

But it’s unlikely that city and state officials will be able to make significant changes to speed limits once everything is said and done. And there’s a reason for that. It’s because neither officials nor engineers really set speed limits. Drivers do.

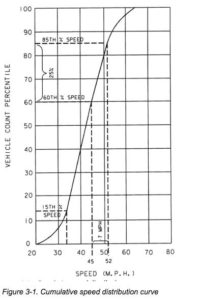

About 60 years ago, America changed how it sets speed limits in this country. Around the country — and especially here in Texas — the way we decide how fast people should drive is through something called the 85th Percentile Theory. It’s this engineering theory that is pretty much dogma now.

“The basic way of using that methodology is that you assume that 85 percent (of) drivers on a roadway are using a safe and prudent speed,” says Kelli Reyna, a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT).

The way the 85th Percentile Theory works is that it assumes drivers 1) are reasonable and prudent, 2) want to avoid a crash and 3) want to get to their destinations in the shortest possible time. With those assumptions, we set limits around the speed that 85 percent of these reasonable and prudent people are driving.

“The thought is, for the most part, people travel at a speed that they feel comfortable with and safe (with),” said Eric Bollich, managing engineer at Austin’s Transportation Department.

Bollich said Austin — like pretty much every city in the state — also uses this method for calculating speed limits. That’s because this is a federal engineering guideline. He points out, however, that even though it’s the main way we set limits, his agency, in some cases, looks at other things like curves in the road, existing bike lanes and driveways.

An illustration of the 85th Percentile Theory in an online engineering manual published by the Texas Department of Transportation.

CREDIT TxDOT

But all in all, this theory leads to major decisions about the speed limits we post.

Billy Fields, an assistant professor of political science at Texas State University, thinks we are doing speed limits all wrong.

“The opposite way of looking at it is why don’t we design our roads for the speed we want people to go?” he asked.

Fields is an expert on how transportation and urban planning can mitigate problems like traffic fatalities. He says he’s pretty skeptical of a lot of practices we developed decades ago. That includes this 85th Percentile Theory.

“The very limited set of research that I have seen on this basically says that a lot of that early research wasn’t highly scientific, and that research then gets embedded in our practices, and it becomes the status quo, and it is so difficult to dislodge the status quo,” Fields said.

Fields is a big proponent for bringing speed limits in Austin’s residential areas below 30 miles per hour. He says that at 30 miles per hour, pedestrians have a 50 percent chance of dying if they are hit by a car.

“That is really problematic, because most of our streets are above 30 miles an hour,” he said.

In comparison, at 20 mph, you have a 10 percent chance of a fatality.

However, a 20 mph limit in residential areas is nearly impossible to achieve right now in the current system we have.

The state legislature only recently started allowing municipalities to post 25 mph speed limits. But to do that — and this is important — the city needs to conduct a traffic study using the 85th Percentile Theory.

“We get requests to look at speeding in neighborhoods, and we take a look at 25-mile-an-hour streets and 30-mile-an-hour streets, and they generally come out about the same 85th percentile speeds,” Bollich said. “That’s just kind of more evidence that just lowering the speed limit won’t necessarily have a large impact.”

These kinds of studies can stop a proposed speed limit change right in its tracks.

Let’s say someone lives near a state road where the speed limit is 60 mph. But let’s also say there is a growing neighborhood around it, and a concerned person thinks it should be lowered to 50 mph. So, TxDOT sends out an engineer. The engineer records the speed cars are going and they find out that 85 percent of drivers are actually going 65 mph. In this case, they can’t lower the speed limit.

“We have to follow what the speed study tells us,” Reyna, from TxDOT, explains. “So if the majority of people are flying through an area where people want someone to slow down, that’s where we come back to following all state laws.”

In fact, if 85 percent of folks were driving 65 mph on a road with a limit posted at 60 mph, the state could very well go back and actually increase the speed limit.

“That’s our job — to make sure that the roads are as safe as possible. And, you know, there are disadvantages to setting speed limits too far below the 85th percentile speed,” Reyna said.

The argument here is that setting the speed limit below that 85 percent mark can make the road less safe because it goes against the natural flow of traffic, or how people feel most comfortable driving.

Ultimately, Reyna says people need to watch their speed on the road because the safety of roads in this case is up to drivers. And because of our policies, that’s literally true.

But Fields says that leaving something as important as speed in the hands of drivers — or even law enforcement — is short-sighted.

“Enforcement seems like the easy place to handle this,” he explains. “You want enforcement. You can’t not have enforcement. But underlying this is engineering design lines and guidance, and that’s harder to change, and we tend not to focus on it as much.”

“But speed is the crucial factor,” Fields continues. “We shouldn’t have high-speed traffic in our neighborhoods and when you do, we have a fatality problem.”

TxDOT and city transportation officials say they want drivers to be safe on the roads and that this is the most important part of their jobs. Both Reyna and Bollich stressed how important safety is to their respective agencies.

In Austin’s Vision Zero plan, officials identified high speeds as one of the main culprits for traffic deaths.

The plan, which is currently only a draft, calls for speed studies and a way to work with local and state governments to lower “default speed limits.” Other suggestions stress the need to make sure folks are complying with current speed limits.

In the community feedback section of the report, a local activist wrote a note that said, “Lowering speed limits is not a radical idea, and if even a Vision Zero Action Plan can’t call for under 30 mph speeds, then this plan is doomed to fail.”

This story is part of KUT’s series, The Road to Zero, which explores traffic deaths and injuries in Austin and the city’s plan to prevent them.

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?