Newsletter Signup

The Austin Monitor thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Most Popular Stories

- City leaders evaluate surprising ideas for water conservation

- Audit: Economic official granted arts, music funding against city code

- Parks Board recommends vendor for Zilker Café, while voicing concerns about lack of local presence

- Dozens of city music grants stalled over missing final reports

- Council reaffirms its commitment to making Austin a more age-friendly city

-

Discover News By District

Popular Whispers

Sorry. No data so far.

Why driver distraction is a persistent problem that defies easy solutions

Friday, May 13, 2016 by KUT News

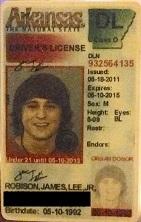

On Jan. 13, 2015, at about 9:30 p.m., 23-year-old James Robison was driving his motorcycle on Riverside Drive toward downtown.

On the other side of the road, the driver of a Ford Focus had just gotten to Austin from Killeen. He and his passenger had come down to help a friend shoot a music video. They had put their friend’s address into a GPS app on his phone.

They were about half a mile from where they were going. And then, a wrong turn.

With the phone on his leg, telling him to make a U-turn, the driver turned the car into the left turn lane.

As they turned, the passenger gasped. The driver closed his eyes. Then, the crash.

The driver never even saw James Robison on his motorcycle. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

“That was the only thing that the (driver) admitted. They said, ‘I didn’t see them, I was on my GPS device at the time,’” says Austin Police Commander Art Fortune, who heads the Highway Enforcement Division. This crash was somewhat unique because distraction played a provable role in what happened.

Austin’s Vision Zero task force identified distraction as one of six main factors that lead to fatal or serious-injury crashes. But especially in fatal crashes, it’s not so easy to prove it to a certainty.

“I would say distractedness probably plays a major role in a lot of things, but it’s just so hard to prove because people aren’t going to admit to it,” Fortune says.

Police just can’t know what was happening at the time of a crash, especially in cases where possibly distracted drivers were the only ones involved and they died.

Look through police crash reports from 2015, and you’ll see some that could be caused by distraction.

One police report from a fatal car crash on Jan. 27, 2015, reads: “For unknown reasons, the vehicle left the roadway and struck a cement pillar.”

On Sept. 5, 2015: “Left the roadway and crashed into trees.”

Nov. 14, 2015: “Left the roadway and struck a tree.”

We’ll never know exactly what happened in these cases. But looking at all crashes, not just the ones in which someone died, between 2010 and 2014, distraction or driver inattention was the No. 1 contributing factor.

Here’s the crazy thing: We all know this. We know using your phone while driving is really dumb. It’s dangerous. When you’re using your phone behind the wheel, you’re about as impaired as if you’ve had several alcoholic drinks.

But we do it anyway.

“The problem with a lot of things like texting and driving is it’s not a guaranteed problem,” says Art Markman, a psychology professor at UT-Austin. “Nobody plays Russian roulette with a gun that’s full, right?”

Markman says that because the probability that we’ll be in a crash because we’re distracted is relatively low; in the moment, we act as if the risk is zero. But, of course, it’s not.

So what do we do about it?

The city put a new law in place last year banning handheld devices while driving. Austin police have written about 7,000 tickets since they started enforcing that law last February. Yet, at least anecdotally, the problem is only getting worse.

Markman argues that these kinds of laws are little deterrent for people using their phones while driving because the probability of being pulled over for texting and driving is so low.

“Afterward people go, ‘I shouldn’t have been doing that,’” Markman says. “But in the moment they are thinking, ‘Well, I’m not going to get caught doing this.’”

According to a 2013 study from the University of Wisconsin, laws banning phone use while driving only seem to serve as a deterrent for a few months after they’re put in place. But another study out of Texas A&M in 2014 found that texting bans in 19 states between 2003 and 2010 resulted in a 7 percent reduction in hospitalizations related to car crashes.

Austin police have recently started to crack down on violators of the hands-free law. They’ve started riding around in empty Capital Metro buses to spot people on the highway using their phones while driving.

What can we do to stop it?

People like Mike Myers say we should be doing more.

“One is that we do need to continue doing more on outreach and education around distracted driving,” Myers says. “We need to re-look carefully at the driver education process. And the third thing is we do need a statewide law for hands-free driving. We have a patchwork in Texas. That’s not acceptable.”

Myers has been thinking about this stuff for a while. Ever since April 9, 2014.

That’s the day his daughter died.

Mike Myers with a photo of his daughter, Elana. She died in a suspected distracted driving crash on April 9, 2014.

CREDIT JORGE SANHUEZA-LYON/KUT NEWS

Myers’ daughter, Elana, graduated from Bowie High School in 2013. She was in her first year at Texas Tech. She was just shy of her 19th birthday on the day she headed home to Austin from Lubbock. She never made it.

“Middle of day, nice weather, single-car crash,” Myers says. “She lost control of the car and went over an embankment and rolled it. But they said it was classic of somebody also that had looked away.”

It’s not clear exactly why she looked away.

“Elana was very smart. But we also know that that phone was always by her,” Myers says. “We don’t know what happened. We don’t know exactly, did she look at that phone, did she start to grab it. But we do know that this wasn’t caused by bad weather or anything else. It was a mistake that within a couple of seconds took her life.”

Since his daughter’s death, Myers has become an activist on the issue of distracted driving. He wants more education and stronger enforcement.

What about engineering?

Austin’s Vision Zero plan recommends looking at how other cities enforce their hands-free laws. But that’s really the only recommendation aimed specifically at distracted driving. The Vision Zero philosophy says it takes education, enforcement and engineering to reduce traffic deaths.

Which left me wondering: Is it possible to solve this problem with engineering?

I put that to Billy Fields, who studies transportation policy, among other things, at Texas State University and is a member of Austin’s Vision Zero task force.

He says the typical engineering approach is to build wider roads to create buffers.

“So we create lots of space. And what happens is if you make a mistake” — say you’re distracted — “you can have room to correct,” says Fields.

“The problem is that that also is the same type of space that increases speed,” says Fields. “And then you have a really big problem, because speed is the biggest contributor in terms of fatalities. So when you have high-speed wide lanes, we have problems.”

Especially when a driver is distracted.

It’s not just texting. There are all kinds of distractions: looking away from the road, taking your hands off the wheel or just taking your mind off of driving. Phones are just especially bad because they distract in all three of those ways.

“A counterintuitive way to think about this is you actually design narrower and tighter lanes. And what happens is that people are forced to pay attention,” says Fields. “They drive slower. And then, if there’s a mistake, that mistake doesn’t contribute directly to a fatality.”

So, narrower lanes can lead to safer driver behavior, Fields says.

There’s nothing specific in Austin’s Vision Zero draft plan about designing roads to discourage distraction. More enforcement appears to be the main idea for addressing the problem. It seems distraction is one of those kinds of bad driver decisions that defies simple solutions. To some degree, the choice is ours.

Myers told me something that stuck out about that.

“As a father, I couldn’t help her,” Myers says. “So that image that I have of her packing her things in the car and making sure that she had the battery cables and knew what to do and knew who to call, none of that mattered.”

As prepared as he made sure Elana was, she made a mistake. It’s a mistake that a lot of us make. Maybe one that some of us have already made today.

Sadly, it ended up costing Elana Myers her life.

It’s unclear what effect Vision Zero will have on distracted driving here in Austin. Maybe that part is just up to us.

This story is part of KUT’s series, The Road to Zero, which explores traffic deaths and injuries in Austin and the city’s plan to prevent them.

Top photo by GABRIEL CRISTÓVER PÉREZ/KUT

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?