After quarter-century on court, Gómez sees pros and cons in change

Thursday, January 2, 2020 by

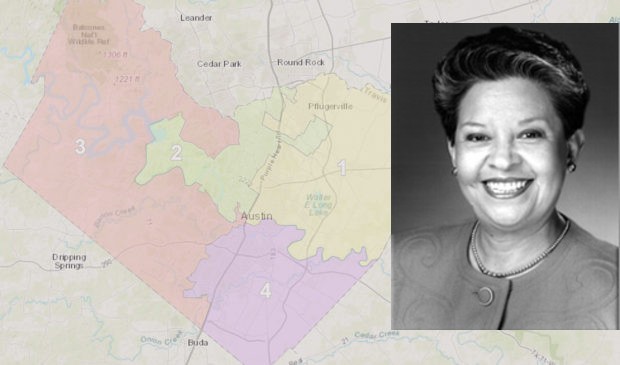

Jack Craver Margaret Gómez has served on the Travis County Commissioners Court for 24 years, representing a precinct whose boundaries roughly correspond with the southeastern quadrant of the county, including nearly all of South Austin east of South Lamar Boulevard.

Her career in county government began two decades before her election to the court in 1994. In 1973 she was hired to work for then-Commissioner Richard Moya, the first Latino elected to public office in Travis County, and in 1980 Gómez was elected constable.

County government operated very differently in the 1970s and ’80s, Gómez recalls; it was far less centralized, with each of the four commissioners overseeing infrastructure projects for their precincts. There were four separate precinct headquarters for constituent services as well as storage for road-building equipment. The county did away with that system in the late ’80s, says Gómez, in part to save money on heavy equipment.

She believes the new system has its pros and cons. She regrets the absence of precinct offices where constituents could interface directly with their elected officials. Now that the budget isn’t formally divided between precincts, “You have to be really, really careful that you’re addressing everybody equally,” she says.

One area that has clearly improved, she believes, is the criminal justice system. Unlike many other neighboring counties in Texas, “We don’t do that debtor prison thing,” she says, referring to Travis County’s practice of not requiring cash bail for most of those booked into jail after an arrest.

“I don’t know that a lot of people know that,” she notes.

Asked about recent accomplishments, Gómez highlighted the court’s recent action on Las Lomitas, a colonia in southeastern Travis County whose several dozen residents get their water from a spigot at a nearby county facility. The county had sold the water at an extremely discounted price – 25 cents per 100 gallons – and the Commissioners Court sought to raise the price to reflect what it cost to provide it: $12.28.

When residents poured into the court to say that the price hike would be devastating, the commissioners decided to delay action. They ultimately opted to go ahead with the price hike, but county staffers are tasked with coming up with a discounted rate to offer those at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty level ($38,625 for a family of four) before the price hike takes effect in March.

The long-term solution, however, which Gómez says is overdue, is for the county to start serving the homes with running water. “They’ve built their homes. And they’ve done a pretty good job,” she said of the residents, who are predominantly Latin American immigrants. “They’re not just squatters, they’re taxpayers.”

Gómez, 75, grew up in Bouldin Creek in a blue-collar, Spanish-speaking family. She has watched with sadness as neighborhoods that were once home to working-class Hispanic communities have gentrified.

“Gentrification has a tendency to move people who have lived in those areas for a long time out of the way. It kind of really changes the makeup of the community a lot,” she says.

Hence her support for preserving the Palm School building, which until the 1970s was an elementary school serving the children of the predominantly Latino community of the Rainey Street area, before it transformed into an entertainment quarter. A group of activists have been campaigning to prevent the county, which for four decades has used the building to house its Health and Human Services department, from selling the property to a private entity.

During the debate over the property, Gómez stressed her support for preservation and has said the county and city of Austin should collaborate to turn the Palm School into a cultural center. She has not offered specifics on how that effort would be funded and it remains unclear what will happen to the building. While the court has approved restrictive covenants that will bar any future owner from demolishing the building, some commissioners, notably County Judge Sarah Eckhardt and Commissioner Gerald Daugherty, want the county to get some money out of the deal.

“We keep losing properties that I think are very reminiscent of past days,” Gómez says wistfully, explaining her support for protecting the property from redevelopment. “Things that most neighborhoods and people have gone through.”

Asked about the effect of the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown on her precinct, which is home to a large immigrant population, Gómez says it has created a “tremendous amount of fear.”

“We have folks from Mexico, and from Latin America, and most of those issues are about folks trying to escape violence,” she says. “It’s just unbelievable. They want to be here, they want to go to school, they want to build homes. It’s been very maddening to me that we have to be so mean in our approach to asylum seekers.”

Like all of her colleagues on the Commissioners Court and City Council, Gómez was deeply disappointed by the tax caps on local governments put in place by the GOP-led state Legislature.

“That was very rough to believe that it was happening,” says Gómez of the state’s move, which forces the county to seek voter approval if it wants to increase the effective tax rate over 3.5 percent in a year. “Nothing like that has ever visited us. We have to be very, very careful how we handle that.”

The Austin Monitor’s work is made possible by donations from the community. Though our reporting covers donors from time to time, we are careful to keep business and editorial efforts separate while maintaining transparency. A complete list of donors is available here, and our code of ethics is explained here.

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?